New Beginnings and the Rebirth of Art?

ARGUING FOR A FLUID RENAISSANCE

There has been a long tradition amongst art historians to see the beginning of the Italian Renaissance as the demise of the Middle Ages, characterised by a sudden rise out of a cultural abyss and into an age of enlightenment, innovation, scholarship and modernity. This rinascita (rebirth) reputedly bursting forth fully formed like Athena from the head of Zeus ready to be laid securely in its Florentine cradle. The Great Age supposedly represented a paradigm shift, a time of swift progress, rapid assimilation and large scale regeneration, predicated on the idea of sweeping away all that was brutish, uncivilised and ugly replacing it with the grace and purity of the all’antica, looking, paradoxically, even further back, to the classical past. But increasingly that’s being seen as a well worn myth. I argue the case for continuity as much as change, for a gradual adjustment instead of abruptness, for congruence as opposed to divergence. Not so much rebirth and new beginnings, more a fluid metamorphosis with many diverse narratives.

In the 1880s sitting in a draughty and high vaulted lecture hall in the University of Basel listening to the eminent professor Jacob Burckhardt you would have been familiar with the new concept of a Renaissance in art, he coined the phrase, well appropriated it really from Giorgio Vasari and from the historian Jules Michelet, but without doubt he put the word into our collective consciousness. You would have heard Burckhardt extolling his vision of the Renaissance as one of violent change, politically, socially, religiously, culturally and artistically. A full stop or at least a semi-colon between the superstition and childlike ignorance of the Medieval past pushed away to usher in a new dawn of modernity. And he was a great orator, persuasive in his vision of change and eradication and it was taken up by the art history world as gospel. So, with some qualifications, that vision, his much studied thesis, is one which has been widely taught and is followed by the art history world and in many museums, who still unknowingly demonise the Middle Ages ( the medieval gloom of the “dark ages in the middle”, between the Classical era of ancient Rome and Greece, and its Revival) or the harshly named Dark Ages (where we were, seemingly, fumbling in the dark), and thus emphasising the elevation of art from the , by extention, substandard Gothic, to the majesty and excellence of the Quattrocentro.

6th Century Coptic Icon Christ and Abbot St Menas, Louvre

Words are potent and any legacy is driven by the labels pinned upon it, especially when linked to a great narrative. Burckhardt’s theory although seminal in the art history world, and in its terminology, was also backward looking in its framework. The Italian peninsula, and Florence in particular, worked hard to place themselves at the centre of the new order. The Medici certainly drove the narrative: did their legendary status fuel the myth that the “Renaissance” gave birth to modernity as we know it? Certainly the economic and socio-cultural growth in this period, linked as it was to the great households such as the Medici, the Gonzaga, the Este did make this period, in retrospect, appear like a new era.

But was there really a pivotal moment in the revival of European culture or should we think of this period in more fluid terms? Is Burckhardt’s perspective too simplistic? . Can we discern a distinct line in the sand as the shift is made from Medieval to Classical revival or is there a broader timeframe where the two traditions existed side by side: a more complex and dynamic interplay of influences and ideas happening, a transitional phase, melding old with new, tradition with revival? Or indeed did the Renaissance begin to appear long before the ism is commonly thought to have begun? Let’s try to answer some of these questions and examine the case for a fluid Renaissance.

Cimabue Trinity Madonna 1288-1292, Uffizi Florence

Consider Cimabue’s stunning Madonna Enthroned, painted in the late 13th Century. Too easily dismissed as a Byzantine relic this painting is truly a transitional piece, a synthesis of a traditional hierarchical composition, gold leaf and drapery with a more naturalistic approach, innovative spatial composition and a shifted theological context where the Madonna is presenting as a more accessible and sympathetic persona, inviting connection. Baxendall (1991) describes Cimabue’s Madonna as ‘encapsulating the synthesis of spiritual authority and evolving naturalism, as a bridge..’ (1) linking Medieval to Renaissance art forms.

So it would be naive to think medieval artistic practices disappeared overnight, but how long did they linger? Traditional practices certainly persisted well into the 15th and even in some cases 16th century. Thematically especially the change was slow. Iconographic elements from the Medieval period continued to be desirable to patrons. Spatial and religious contexts therefore continued, albeit with a nuanced evolution. Take Fra Angelicos Linaiuoli tabernacle from 1433. The Madonna is depicted within a chamber draped in cloths of gold. There remains a stiff formality in her posture adhering to Medieval conventions and surrounded by ornate gold leaf especially in the background and halos, forgoing the importance of naturalistic representation over spiritual experience, again a hallmark of medieval aesthetics. She is, in effect an homage to the Byzantine icon.

Linaioli Tabernacle Fra Angelico 1433, Museo San Marco Florence

Altarpieces seemed, not surprisingly, to be the last to give way to changes. Congregations looked to the altarpiece to lead their prayer and explain the Biblical narrative. The altarpiece needed tobe visually arresting as well as easy to comprehend. The polyptych form lingered not just in provincial areas but also alongside more modern pieces in the innovative centres of art.

A mere 50 years before Titian produced his incredible Assumption of the Virgin in the Basilica S.Maria Gloriosa dei Frari, in Venice, Giovanni Bellini had painted the St Vincent Ferrer Altarpiece for the Santi Giovani e Paolo less than a mile away. These are two totally contrasting pieces. The Titian with its mastery of colour and light, its pyramidical composition, emotional expression, naturalistic imagery and dramatic use of space exemplifies the new Renaissance. It was though somewhat controversial at the time which in goes some way to explain why in Venice the more traditional layouts were slow to disappear. The Vincent Ferrer Altarpiece successfully retains the traditional format through its multi-panel structure, religious themes, and established iconography displaying artwork that is firmly rooted in the conventions of much earlier medieval altarpieces. However while the polyptych adheres to the traditional religious formats, it subtly begins to incorporate humanist ideals that might challenge strict religious orthodoxy.

St Vincent Ferrer Altarpiece, S Paolo e Giovanni, Venice, Giovanni Bellini 1464-70

Later still is Bartolomeo Vivarini’s Conversano Polyptych. Another Venetian, Vivarini, was on this occasion producing a piece for a town in the South of the Peninsula. It was started as late as 1475 yet still follows a very traditional format and sits within a highly decorative gothic frame. It comprises multiple panels, with a hierarchical structure placing Christ at the top the Virgin and Christ child central in a narrative tableau depicting the Nativity and two layers of saints, each with identifiable attributes that align with traditional iconography. The saints do show a degree of humanism and there is some backstory included, however, trapped as they are in their panels, they do not interact and the piece feels didactic rather than interactive. Gold ground dominates the whole with the saints placed against visible gold haloes. This is a piece stuck in the 14th Century.

Bartolomeo Vivarini, Conversano Polyptych, 1475, Accademia Venice

And then there is Carlo Crivelli who in his provincial backwater of the Marches kept the polyptych style going, albeit in subverted form, long after it had died out elsewhere One gets the feeling though he painted a sacre conversazione and chopped it up to fit the frame like a collage. Examine this exquisite Altarpiece of Mount San Martino completed in 1480. One feels the irony dripping palpably off the piece.

Crivelli, Altarpiece of Monte St Martino 1480

The practice of fresco has a strong medieval and even ancient lineage. As a technique it has its limitations: the working time is short as the plaster dries quickly, the pallet is restricted, the practice irreversible and most importantly the resulting fresco is highly susceptible to damage. Yet there are some notable uses of the technique well into the 16th Century and even beyond into the “Baroque” (another terrible moniker) : the ceiling of the Sistine chapel, the Villa Farnese, The Doge’s palace in Venice, Pozzi’s ceiling in the Sant’Ignazio Church in Rome to name just a few of the more prominent works. What we are essentially looking at here though is not the same technique, but by using innovative new pigments that were more stable, glazing techniques that gave the works a richer visual effect it was much improved. The popularity of trompe d’oeil must have been influential: the theatricality and narrative complexity of Correggio’s ceiling in Parma Cathedral could not have been achieved in that space without using fresco, the figures seem to float in the celestial sphere and burst straight out of the confines of the dome.

Correggio, Assumption of the Virgin, Parma Cathedral, 1530

And what of the signposts that art historians believe heralded the Renaissance? No one is naive enough to think these sprang ready-formed on to the scene like like Venus rising from the sea, born from the foam, radiant and complete in her divine beauty. Yet there is a sort of assumption that the assimilation of these changes was rapid and that prior to the magical date they were non existent. Is this the true narrative or merely a useful hook that’s easy to hang a hat on?

The Burkhardt story weaves the tale of a renaissance blossoming in Florence infused with the spirit of humanism igniting a totally new artistic expression. Think of Leonardo’s Last supper in the refectory of the convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie (in Milan but Leonardo da Vinci was Florentine) with its chiaroscuro creating depth and realism and heightening the Benedictine monks experience of the Biblical narrative as they set their bread and cheese. But all these elements are nothing necessarily new. Think of the Lindisfarne Gospels (c 700 CE), the Saint Savin frescoes (1060) or the magnificent Christ Pantocator in St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai. Go on, have a guess when it was painted? (2)

Christ Pantocator, St Catherines Monastery, Sinai, date in footnotes

Burdkhardt and Vasari agree resoundlingly on one point: the Renaissance began in Florence. Likewise for Gombrich Florence was a universal standard. Today the Florence tourist information even boasts as its tag line “Cradle of the Renaissance”. But is this just a beautifully curated myth? Did the ideas permeate out from Florence or did they erupt in different geographical points across Europe or indeed the World? When Vasari wrote his “Lives” he was in the employ of the Medici. He elevated his patrons alongside the artists they employed. The Medici family's influence was profound and multi-dimensional, encompassing patronage of the arts, strategic political manoeuvring, and the promotion of humanist education. Their financial support of artists and scholars created an environment conducive to artistic and intellectual exploration, while their political strategies helped establish stability in Florence, allowing for this cultural flourishing. The Medici wanted to transform Florence into a beacon of artistic innovation, and they drove the narrative, they made the rules. But, though it cannot be argued that Florence was one centre of innovation, was it the only one? Vasari, of course, towed the party line, effectively dismissing anyone outside of the city walls as inferior: he even had a second tier for those unlucky in birth. But is a Florentino-centric view the only view? But the greatest humanists were not natives of Florence at all. Petrarch (3) was from Arezzo, Ferreto de Ferreti from Vincenza, Colonna form Avignon, Erasmus from Rotterdam, Lefevre d’Etaples from Picardy, Filastre from La Suze in France, John Hus from Prague.

Virgin and Child with Canon van Der Paele, Jan Van Eyck, 1436

Not all artistic innovators came from Florence either, though it is true the Medici did draw many of them into the City with promises of fame, fortune and artistic freedom. Artistic developments popped up all over Europe. Leon Battista Alberti hailed from Genoa, Mantegna from Padua, Lorenzetti from Siena. Jan Van Eyck is an important point in fact. He is described as an early bridge between the Gothic and the Renaissance and originally developed his style independently of the innovations happening on the Italian Peninsula. He is credited with introducing oil paint (another great marker of the start date for the Renaissance) and whilst I agree he certainly perfected its use it had been used quite extensively in Northern Europe form many years prior to him. However there is no question it is a Northern innovation and not a Florentine one. Van Eyck incidentally declined offers to work for the Medici. He worked at the Burgundian Court of Philip the Good, who clearly did not have such a good publicist as Cosimo Medici and he has in the public eye slipped into relative obscurity. However Philip played a truly pivotal role in shaping the Renaissance, particularly in Northern Europe. Philip's court was a centre of humanism, where scholars came together to exchange ideas. This intellectual climate encouraged the study of classical texts, supported the establishment of educational institutions and was involved in the promotion of literacy and scholarship. The Burgundian court fostered a vibrant cultural milieu through patronage of the arts, and support for humanist scholarship, and as a by-product he created a politically stable and economically prosperous state. The Burgundian Netherlands, was not insular either. It became a significant cultural crossroads, facilitating interactions between different regions dispersing art and ideas generated in his court throughout France, the Low Countries, and even towards Italy. Burgundy, true cradle of the Renaissance?

Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, near Pompeii, 1stC BC

The development of linear perspective is cited as the hallmark of Renaissance art, attributed to Brunelleschi as late as 1415. However the groundwork for these techniques can be observed in much earlier practices. Giotto di Bondone in his Ognissanti Madonna showed a clear understanding of spatial depth and volume as early as 1310. Even further back we see a pragmatic understanding of that lines parallel to the viewers line of sight converge: frescoes at the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale, near Pompeii although they violate the rules of one point perspective show a clear understanding of the basic rules of orthogonals.

And did everyone take up this technique? Well the answer is a resounding “NO”. Even artists well aware of its existence, such as Jan Van Eyck (I’m thinking his Arnolfino Portrait here with at least 4 different vanishing points), purposefully ignored it for stylistic or compositional reasons. It didnt seem to be used consistently either by individual artists. Raphael employed it strictly in his School of Athens where Plato seems to put out his hand and pull the whole image towards him, yet in his Sistine Virgin painted three years later he totally disregarded it on stylistic or more likely positional grounds. Raphael in fact can be seen as something of a poster child for the disregard of perspectival devices. Raphael basically liked to break the rules. In his Marriage of the Virgin the viewer hovers somewhere in space above the heads of the crowd. In The Transfiguration, the figures crowd the foreground and are arranged in a totally dynamic, almost theatrical manner, which has disrupted the perspective. The emphasis here is more on the emotional impact and dramatic tension than on strict spatial organisation. But do his paintings look unbalanced? Well, no. And I suspect that is because he understood the rules well enough to break them. Isn’t that the true sign of a master?

Manuscripts, especially, were slow to catch on. The De Sphaera Manuscript of 1450-60 disregards rules of perspective and realism in order to include as much detail as possible. One can clearly see that the artist understood the rules yet chose to disregard them.

De Sphaera Manuscript of 1450-60, Biblioteca Estense Universitaria, Modena

One cannot consider the Renaissance without paying attention to the shift in genres. An oft stated sign of the new era was a greater attention to secular subjects, including portraiture, landscapes, and daily life, as well, of course, of the return to classical and mythological subjects. Allegory was big in the Renaissance. Every household wanted a spalliere in their bed chamber depicting a great mythological event. Even better if it included naturalistic animals and anatomically accurate posturing nudes. Piero di Cosimo’s Forest Fire spalliere and its pendant pair Return from the Hunt depict very raw images of primeval forests, violent, brutish and strangely unnerving scenes of death and confusion in one and joyful abandon in the other. However, in some ways the panels tick the boxes of what the humanist wanted on his wall. There is a huge level of detail ( these are paintings designed to be examined up close (shoulder height)), the literary references are there: Lucretius treatise "De Rerun Natura" and Vitruvius are the catalysts, a certain wit (are those the faces of the patrons?), and raw emotion. Seen as a cycle they would have had a clearer narrative. Apparently they are part of a set of at least 5 made for the marriage of Francesco del Pugliese and Alessandra di Domenico Bonsi , that told the story of man's early history struggling to survive and become a civilised being: perhaps when seen alongside the panels where man tames the wilderness and becomes civilised they would have been more acceptable as decoration in a bedchamber.

Piero di Cosimo’s Forest Fire, 1505, Ashmolean Museum Oxford

But religious works still dominated albeit in altered form. Iconographic elements prevailed but other more humanist elements were included. In fact across the board there were new elements added to works of art.

The incorporation of rich symbolism enriched paintings with deeper meanings. We see balanced and harmonious compositions, often using geometric shapes, such as triangles, to create a sense of stability and order. The innovative use of architecture, settings, and backgrounds, gives a sense of space and depth that enhances the narrative. Yet plus ca change plus c’est la meme chose. Hans Memlings Last Judgment is innovative in its realistic expressions, its dynamic composition, its spacial layout. However when you consider the use of colour, the symbolism, the intricate rendering of fabrics and indeed the didactic and thematic composition focussing as it does on salvation and damnation and their clear contrasting imagery it is obvious how much this harks back to the image’s medieval roots.

Memling, Last Judgment, 1467-71, Gdańsk Poland

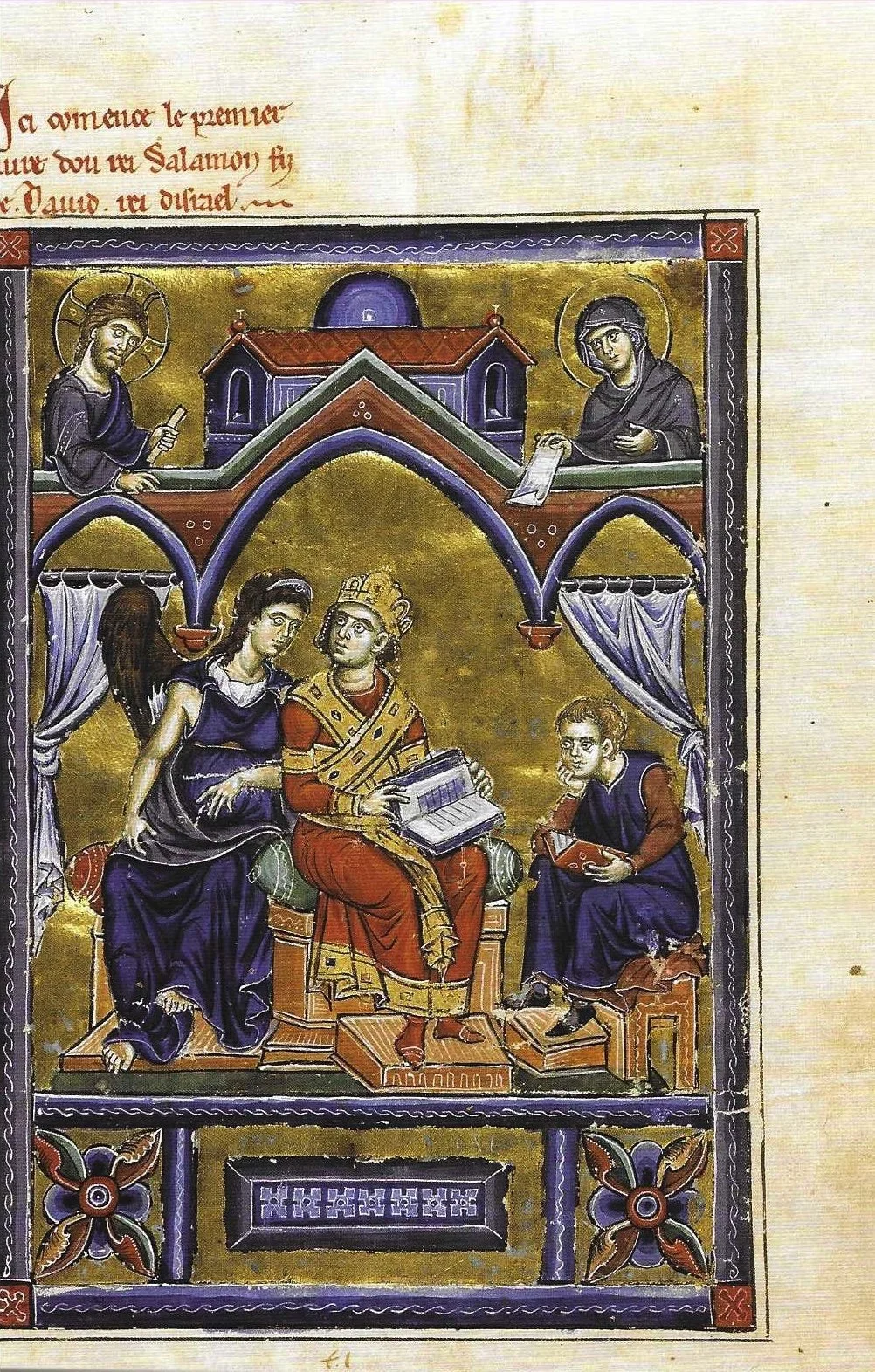

We gaze in awe in front of Raphael’s glorious Madonna in the Meadow with its meticulously thought out triangular grouping, yet consider this stunning folio. Could there be a more overtly and indeed languid arrangement? But here in a manuscript from 250 years earlier.

Frontispiece to Proverbs of Solomon with the personification of Holy Wisdom, Arsenal Bible 1250-54 Biblioteque Nationale de France

One well charted change in the art produced in the Renaissance is the inclusion of a strong narrative voice, and with it often a myriad of detail, sometimes obscuring the subject that, to the modern eye, may not seem overtly necessary. Artists began to emphasise the emotional and psychological states of their subjects featuring characters with expressive faces and dynamic poses. Details were laden with symbolism, allowing for multiple layers of meaning. Iconography became much more complex and nuanced: the message was no longer clear and unambiguous. Gone was the stylised and abstract symbolism, prioritising spiritual significance over realistic representation and instead appeared iconography that was more lifelike infusing symbols with a sense of reality and depth. The artists voice was heard much more clearly and individual artists created their own inventories of symbols. Paintings, especially in Northern Europe, became chaotic and dynamic visions, where the eye could wander in search of meaning and context. It took effort sometimes to find the meaning in a painting and, as artists were given the freedom to be more expressive, art became crowded with extra figures, architecture details, and as in the case here by Jacob Cornelisz van Oostanen in his Adoration of the child, miniaturised landscapes that personalise the piece for the patrons. I want to share this lovely description from James Snyder “countless angels, like hoards of kindergarten playmates, invade the centre of the picture and wildly sing, play instruments and dance about the trough of the tiny Christ as if celebrating his birthday.” (5)

Jacob Cornelisz van Oostanen, Adoration of the child, 1515, Art Institute Chicago

But was the narrative voice missing in medieval times? Did the Bayeau Tapestry lack a narrative? And what about devotional sculptures or stained glass? And If we look at manuscripts from as early as 600 CE they positively teem with narrative detail. The limitations of painting techniques at the time meant it was only in manuscripts that such detail was practical, but the extent to which it dominates this medium shows how desirable it was long before oil paint made its use widespread in the Renaissance.

The Utrecht Psalter 820-835 CE, Utrecht University

Whilst the Renaissance is often cited as a monolithic movement in art this perspective oversimplifies the complexity and diversity of the period as it is in fact a collection of diverse practices influenced by regional variations, cultural exchanges and evolving social contexts. It is not all about the rise of humanism and one point perspective. On the Italian peninsula the focus was on humanism, classical antiquity, and naturalism in art. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael emphasised proportion, perspective, and human emotion. Yet in the North it was the emergence of detailed realism and intricate symbolism that signalled the change.

Although our focus here is on art it cannot go without mentioning the diverse practices that made up the wider idea of the Renaissance. The Renaissance was obviously not limited to art; it also encompassed literature, science, philosophy, and education, and each developed unique characteristics in different regions.In Italy, poetry and prose were heavily influenced by classical Latin and by newly discovered works, whilst in England, figures like William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe adapted the Renaissance humanist themes to fit their own cultural contexts.There were significant scientific developments of the shaped by local universities, by cultural attitudes toward nature, and by religious beliefs, resulting in multi-varied paths of scientific inquiry all occurring concurrently, but with variations.

Gentile Bellini Sultan Mehmed II, 1480 National Gallery London

Cultural exchange was big influence of the rapidity of change and the role of the East cannot be ignored. Many classical texts were preserved and translated by Islamic scholars during the Middle Ages, and these texts played a crucial role in the intellectual revival seen in the Renaissance. The transmission of knowledge through trade routes and diplomatic contacts fostered the blending of different cultural elements. Further cross-pollination was initiated by war and disease. During the Italian Wars (1494–1559), the migration of artists, scholars, and ideas was particularly significant. Michelangelo worked in several locations due to the shifting political landscape. He spent time in Florence and Rome, adapting his work based on the changing demands of patrons. For instance, he was called back to Florence in 1530 during a period of political strife primarily to oversea the fortifications of the city. Artists had to be multi-talented to thrive!

The Chess Game Sofonisba Anguissola, 1555, national Museum Poznan

An oft overlooked aspect of the Renaissance is the emergence of female artists as persons of influence. I like to mention Sofonisba Anguissola when I list “masters” of the Renaissance. Sofonisba challenged the prevailing gender norms with her innovative portraiture. Her work is often mentioned as a “subversion of the male dominated narrative of artistic creation”. Knox (6) But is that true? I doubt you know much about her or many other women as individuals during this period. The idea of a renaissance did not really have much to offer women. Even influential women like Isabelle D’Este were largely left to subterfuge and trickery to get their needs met. Let’s take a moment to consider how Sofonisba was restricted. As a woman in the 16th Century whilst she was allowed to paint, she was unlikely to be taken seriously. Opportunities for women to receive formal art training were scarce. Although she received guidance from her family, including instruction from local artists, the more extensive training available to male artists was inaccessible to her. She would have found it challenging to secure patronage and being a woman in a male-dominated field made networking and gaining influential patrons particularly difficult. In the Renaissance, portrait painting was one of the few genres in which women could gain some legitimacy as artists but this kept her from exploring broader themes that her male peers might have engaged with. It was perhaps not until Elisabeth Louise Vigee Le Brun in the early 1800s that a woman was truly revered as an artist in her own right, and if we disregard portraiture we must wait until the impressionists for a true gender crossover.

Individuality though is definitely a signaller of the change in era. With it comes the dropping away of reliance on guilds and the restrictions that accompanied them. The Renaissance brought about a shift in the perception of artists from anonymous craftsmen to recognised individuals. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael became celebrated figures and were seen as "geniuses" with unique talents and ideas. Art was a commodity, and market forces trampled on the neat and tidy system of guilds designed to keep it in check. This individual recognition diminished the guilds' importance, as artists sought personal fame and patronage without adhering to the guild restrictions. Wealthy patrons, including nobles, merchants, he Church, and powerful families, such as the Medici began sponsoring artists directly. Whilst guilds had established a structured system of apprenticeships, artists now worked in independent workshops, sought mentorships or entered art academies, emphasising choice, free artistic expression and, also, theoretical study. The guild system did linger though in places. In regions like Flanders and the Northern Netherlands, guilds continued to be influential well into the 16th and 17th centuries.

Francesco Botticini Assumption of the Virgin,1475-6, National Gallery London

So to return to my initial questions. Was there a pivotal moment or should we think of this period in more fluid terms? Was the shift from medieval to classical revival a sudden occurrence or something that took hold over time? Was there a transitional phase where the two sets of ideas co-existed? Is our wish to slap a date on the era too simplistic, ignoring the rich dialogue between innovation and tradition that happened back and forth for decades?

I really believe the notion of a singular pivotal moment fails to encapsulate the complexity of this period; instead, I see a gentle intertwining where the classical revival gradually meshes with existing medieval frameworks, resulting in a rich tapestry of artistic expression. This transitional phase allowed for an intricate coexistence of ideas, where innovation did not merely replace tradition, but rather engaged with it and enriched it through reinterpretation and adaptation.

Our inclination to assign a strict date or delineate clear boundaries around any period of art history is indeed too simplistic, as it overlooks the nuances of artistic development during any transformative decades. The idea of periodisation is a tricky one. It is an idea compounded by modern art history studies where the making of neat self-contained packages sells books and courses. Burke describes the term as “an organising concept that has its uses” (7) but is there a better term? Gombrich’s suggestion of a movement in many ways solves this problem and also incidentally highlights the controversy and fervour the Renaissance and its study ignites in people. Movements are revolutionary are they not?

Likewise what of the idea of Florence as the epi-centre of the change. Scholastic thought is becoming sceptical of Florence as the sole birth place of the Renaissance , but I suspect it will be difficult to overcome the behemoth that is Florentine Renaissance tourism and the desire for art historians to stick to a rigid and chronological plan.

Through this lens, the idea of fluidity, the very act of pushing like water against boundaries, whether they be stylistic, thematic, or ideological, underscores the Renaissance as a movement that thrived on adaptation and transformation. Artists navigated a landscape of evolving aesthetics, and their works reflect the delicate balance between reverence for celebrated ideals and a desire to explore new horizons. As such, understanding the Renaissance requires us to embrace its fluidity, recognising it as a period characterised by a vibrant and ongoing dialogue that laid the groundwork for future artistic endeavours. I like to visualise it as a fluid continuum where influences and ideas flowed and merged like the waters of the rivers intersecting the Italian landscape. It was a time of exploration, of cultural, social and political assimilation and dissemination. A time of learning to swim but also of drowning under the influx of new and often contradictory ideas. Seeing it as a period of fluidity encourages us to embrace complexity and nuance, recognising that great movements do not occur in isolation but are part of an ongoing evolution, shaped by historical, cultural, political and social currents that imperceptibly creep into the collective consciousness gradually diluting the old ideals and sculpting the new.

Master L F San Lorenzo and San Sebastiáno Basilica Cycle, Augsburg